Bodie’s source of gold came from hard rock mining – mining that requires breaking apart ore to extract gold that’s intermingled with the rock. There are many steps to this kind of mining; here are some of the steps:

Ore extraction

Basically, “ore extraction” means digging. Digging for A LOT of solid rock out of mountains. The way you get to that rock is by digging hallways to the rocks that have the most gold in them. Those hallways are called ‘tunnels’ and ‘mine shafts’. Bodie has hundreds of miles of mine shafts. Some that connect to others, some that are short, others that are long and some that are so deep, they fill with water from the water table. Those shafts need to be pumped out so the miners can do their work.

Basically, “ore extraction” means digging. Digging for A LOT of solid rock out of mountains. The way you get to that rock is by digging hallways to the rocks that have the most gold in them. Those hallways are called ‘tunnels’ and ‘mine shafts’. Bodie has hundreds of miles of mine shafts. Some that connect to others, some that are short, others that are long and some that are so deep, they fill with water from the water table. Those shafts need to be pumped out so the miners can do their work.

When a suitable location is found for recovering gold-rich ore, a horizontal shaft is excavated, then a vertical shaft is drilled. The ore is then cut out of the mountain by using large drills and black powder or dynamite, then hoisting those chunks of rock to the surface with ore carts and other bucket rigs. As the ore is removed from the mountain, the tunnels and shafts can become unstable and can cave-in, so they must be shored up to keep the men safe and the tunnels open.

Shoring up a tunnel or shaft means building a frame structure that pushes against the rock walls to keep them from moving. Sometimes blasting with dynamite or earthquakes would cause a small cave-in that could create even more shaking that could bring other walls crashing down. When that happened, miners were killed or trapped without food or water. That was just one of the many dangers a Bodie miner took for getting paid $4 a day.

The Stamp Mill

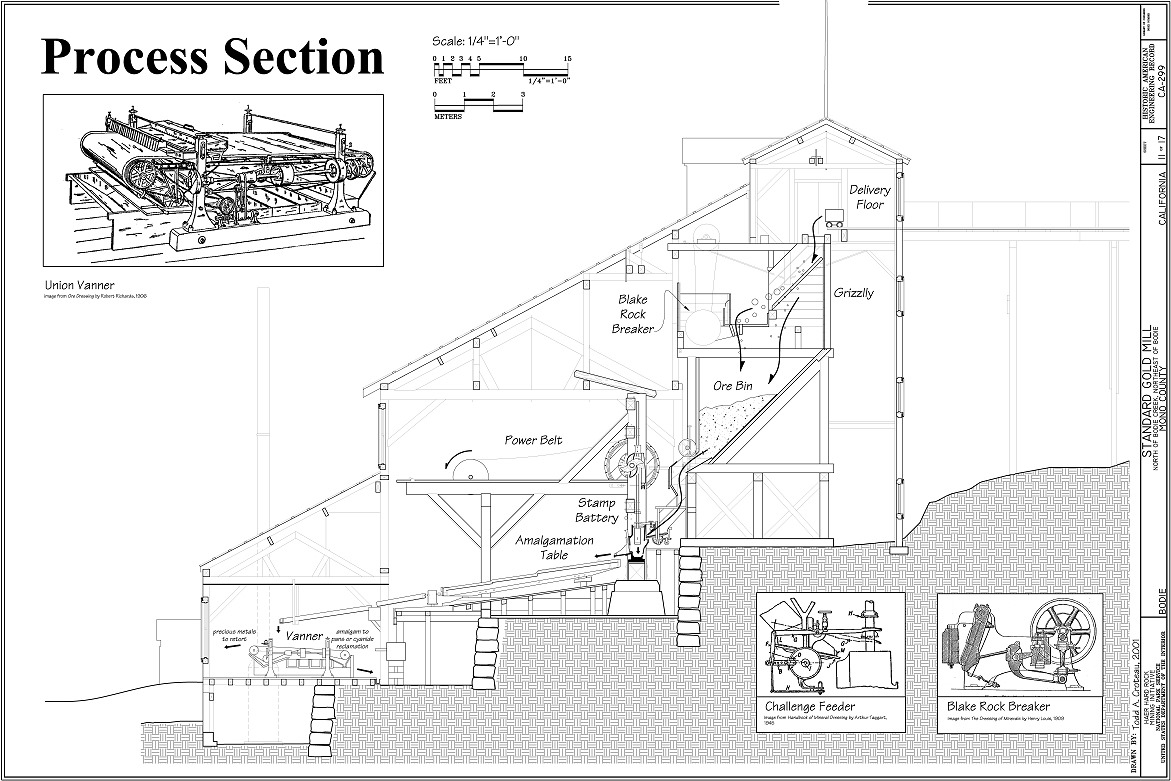

Once the ore was extracted from the mountain, it had to be crushed into a sand-like consistency. A stamp mill has several areas for handling different parts of the process. Stamp mills were usually built on a hillside, located lower than the mines so that the operators wouldn’t have to haul the heavy rocks up to the top of the building – that’s where the process starts…

Once the ore was extracted from the mountain, it had to be crushed into a sand-like consistency. A stamp mill has several areas for handling different parts of the process. Stamp mills were usually built on a hillside, located lower than the mines so that the operators wouldn’t have to haul the heavy rocks up to the top of the building – that’s where the process starts…

At the top of a mill the big pieces of rock, sometimes the size of a soccer ball, were fed into a giant metal jaw that would crush them up until the smaller pieces fell between a metal grating called a “grizzly”; so-called because the spacing between the grating was about the width between the claws of a grizzly bear (about 2 inches). There were sometimes a succession of these crushers that would reduce the size of the ore to the needed gravel sized pieces. The ‘gravel’ would be mixed with water and fed to the ‘stamp battery’.

The stamp battery would further crush the ‘gravel’ into a sand or cinnamon consistency, and was then called ‘slurry’. That slurry would flow out of the stamp batteries through a fine mesh screen onto amalgamation tables. These tables were long and lined with large metal sheets made of zinc. A mill worker would use a brush to paint a chemical mixture of liquid mercury onto the zinc sheets before the sluice was opened on the stamp battery. Then, as the slurry flowed across the zinc and mercury, the gold would become stuck to the plates, while the tailings (the crushed ore that didn’t have enough gold to stick to the plates) would be funneled to tanks, tailing ponds and other holding areas.

When enough gold stuck to the plates, the mill worker would scrape the amalgam of gold (and sometimes silver) and mercury into a big ball, put that into a bucket and give it to the supervisor. The worker would then re-paint the zinc plates with mercury to start the process over. Throughout the day, the stamp battery screens or the stamp die would get clogged and need to be cleaned, so one at a time, stamps would be “locked” from falling while debris was removed. This process of crushing the ore and collecting it by chemical means would get about 90% of the gold out of the rock.

Bodie had a dozen or more stamp mills, with the largest being the Standard Mill. Working in the mill was extremely loud. With 20 stamps pounding away 24 hours a day, 7 days a week (except when a battery was being cleaned) and steam engines roaring and pumping, jaw crushers shattering rocks, millwrights pounding on metal and many other noisy jobs, mill workers were likely to lose their hearing before losing an appendage. One trick workers used was to press bee’s wax with cotton into their ears. But, with an ever present danger from every direction working in such a large building with so many people, so much machinery and moving parts, it might have been more important to hear someone yell “duck”, than it was to keep your hearing.

Recovering the gold

That big amalgam ball of hardened mercury, gold and silver would eventually be delivered to the retort room, where the mixture was heated to melt the mercury to a gaseous form, where it would again liquefy and be recycled back to the amalgamation table in the mill for painting the tables. What remained (hopefully) was raw gold, ready for the smelting process.

Smelting is the process of further refining the gold and melting it into bullion for sale and transportation. Many gold mining towns were targeted by ‘bad men’ and would hold up the stage coaches hauling the gold ingots. Some mine owners in Bodie were smart and poured such large ingots, that a single rider on horseback could not carry a single ingot alone. That helped in reducing stage hold-ups. Another trick by Bodie smelters was to leave gold and silver mixed in a single pour, requiring that it be separated and processed at a mint facility – something robbers wouldn’t be able to do on their own, and if they were looking for facilities to do that kind of work, would surely be discovered.

More on stamp batteries

The battery itself was a large, odd looking iron box with an opening at the top for the stems and an opening on the front that held the fine mesh screens. On the back side of the battery are the cams. The cam shaft was turned by a large wheel, driven by a belt that was turned by a steam engine.A stamp battery is the name for a collection of stamps, usually is sets of 5. Each individual stamp is a heavy round cylinder between 250 and 1,000 pounds each, covered with a ‘shoe’ on the bottom, which is easier to replace than the entire stamp.

The stamp is connected to a long ‘stem’ that can also weigh several hundred pounds alone. Around one portion of the stem is a tappet; a large piece of metal that looks similar to a spool, about 12-16 inches tall. It acted as a lever, which would come in contact with the passing cam and cause the entire stamp and stem to be raised, until it reached the end of the cam and fell. The stem is connected to the stamp, which was covered by a shoe, which drops and strikes the die (or more hopefully, the ore that’s on the die). The die was a flat, hard, round piece of metal, mostly matching the stamp shoe in diameter, where the slurry mix of water and ore would sit until the stamp dropped down and pulverized it.